Over the past two decades, coinciding generally with the election of Gray Davis as governor, the California Legislature has enacted a series of laws that make doing business very difficult. Always cast as an effort to protect the poor, downtrodden employee, these new laws have substantially increased litigation and lined the pockets of enterprising attorneys.

The Private Attorneys General Act, or PAGA, was enacted in 2004. It allows an employee to sue an employer for civil penalties to which the state would be entitled. The employee sues in the name of the state on behalf of himself and for all other similarly situated employees. If successful, employees are entitled to 25 percent of those civil penalties. More importantly, the employees’ lawyer is entitled to attorneys’ fees, a sum that often and easily surpasses the amount of money that goes to employees.

PAGA lists dozens of laws that can form the basis of a PAGA lawsuit. Yesterday, a PAGA lawsuit was filed in Fresno County alleging that on four occasions one year ago an employer paid its employees later than seven days after the end of the pay period. (Costa v. Bottling Group, LLC, Case No. 17CECG01578.) There is no allegation that employees were unpaid or underpaid. The sole allegation is that the paycheck was provided to employees late.

The penalty to the state for this is $100 for an initial violation, and $200 for subsequent violations, per employee, plus 25 percent of the amount withheld. If the employer in the case filed yesterday has 10 employees, the civil penalty would be $1,000 for the initial violation and $6,000 for the second, third and fourth violations for a total of $7,000, plus 25 percent of the amount untimely paid.

Put aside the 25 percent that can be added to the civil penalty. Why is an attorney taking a case where civil penalties to the state are as low as $7,000? Wouldn’t that be considered a small claims court matter? Even if successful, employees would be entitled to no more than $1,750 of those penalties. Why would those employees file a lawsuit and go through the litigation process for such a paltry sum? The only thing I can think of is that some lawyer has snookered those employees into thinking they will make great money. In actuality, the lawyers, not the litigants, make the big bucks!

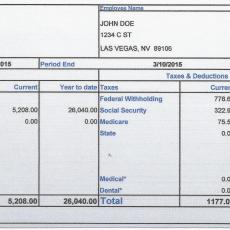

In many cases, a PAGA claim is asserted with personal claims that the employees can assert on their own behalf. For example, an employer with an incomplete or inaccurate paycheck stub is subject to penalties to the employees as well as civil penalties to the state under PAGA. An employee can claim, and recover up to $4,000 for paycheck stubs that lack an hourly rate, the employer’s legal name or address, or a partial social security number of the employee. And of course, attorneys’ fees are available in these personal cases as well.

Other PAGA claims that can be asserted include violations of laws related to unauthorized deductions from checks, meal or rest periods, recovery periods, sick leave, make-up time, alternative work schedule, record-keeping, mandatory day off, overtime, minimum wage, unpaid expenses, etc. Most of the civil penalties under PAGA would result in employees recovering very little money. But the law guarantees that lawyers who prosecute these cases are paid handsomely.

There are defenses and strategies that can be used to defend PAGA lawsuits, and other claims of wage and hour violations. Arbitration agreements can remove some non-PAGA claims to arbitration. Unfortunately, because PAGA lawsuits belong to the state, an employee’s consent to arbitrate a PAGA claim is not enforceable.

An even better strategy is to audit workplace practices to determine whether the company complies with those Labor Code provisions that give rise to a PAGA lawsuit. I recommend that the audit include legal counsel. By including legal counsel, a company can protect information from discovery under the attorney-client privilege and the attorney work product doctrine.